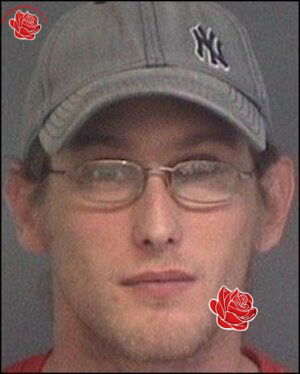

Billy Woodhouse's Social Media Accounts

Know a Social Media Account Linked to Billy Woodhouse?

Want to add information? Log in to your account to contribute accounts and phone numbers.

BILLY WOODHOUSE SENTENCED FOR BRUTAL EYE POKE MURDER IN HAVANT

In February 2002, a tragic case unfolded in Hampshire that shocked the local community and drew widespread media attention. Billy Woodhouse, a 24-year-old man from Havant, was convicted of the heinous murder of his girlfriend’s six-month-old son, Leiton Rowlands. The incident occurred while the child's mother had temporarily left the home to visit the doctor, leaving the infant under Woodhouse’s supervision.According to court proceedings, Woodhouse inflicted fatal injuries on the infant through a brutal assault. The evidence presented in Winchester Crown Court revealed that Woodhouse had violently thrown the child against a hard surface, causing severe head trauma. The injuries were so severe that they resulted in a complex skull fracture and extensive brain damage, ultimately leading to the child's death. The medical experts testified that the force required to produce such injuries could not have been caused by a simple fall, such as falling off a sofa, as Woodhouse claimed. Instead, the injuries suggested that the child's head had been forcefully slammed onto a hard surface, possibly the floor or another rigid object.

During the trial, Woodhouse attempted to explain the incident by claiming that the baby had fallen. However, the evidence contradicted this account, indicating that the injuries were the result of a deliberate and violent act. The court also noted facial injuries and damage to both eyes, which experts attributed to blunt trauma, likely inflicted by fingers or knuckles. The injuries to the eyes and face further underscored the brutality of the assault.

At the time of the attack, the infant was reportedly teething and had been irritable that morning. The child's mother had described her frustration with the baby, having thrown him onto the bed in a moment of impatience earlier that day. When she left at 9:15 am, the child was reportedly content, sitting in his bouncer chair in front of the television after being fed. It was during a 45-minute window following her departure that the assault took place.

At approximately 10:02 am, Woodhouse contacted emergency services, claiming that the child had fallen off the sofa and hit his head. By the time paramedics arrived at 10:13 am, the infant was unresponsive and appeared limp. Despite efforts by Woodhouse, who attempted to resuscitate the child under instructions from emergency personnel, and subsequent medical interventions at the hospital, the baby was pronounced dead at 11:45 am. The medical evidence confirmed that the injuries sustained were consistent with a severe impact, causing a fatal skull fracture and brain injury.

Throughout the proceedings, the court acknowledged that Woodhouse did not have a history of maltreatment towards the child or any other children. The evidence suggested that he cared for the infant and had a desire to adopt him. He was also known to be fond of a son from a previous relationship, with whom he had fought for custody. The court recognized that Woodhouse did not intend to kill the child; rather, the incident was viewed as a tragic consequence of losing control in a moment of frustration.

In sentencing, the judge emphasized the severity of the crime but also considered mitigating factors, including Woodhouse’s age and the absence of premeditation. The starting point for the sentence was set at 15 years, with the minimum term to be served before parole eligibility determined by law. The judge recommended a minimum of 10 years, while the Lord Chief Justice suggested 8 years. Ultimately, the court ordered that Woodhouse could apply for parole as early as March 2009, after serving 8 years of his sentence, less the time he had spent on remand. The decision reflected the gravity of the offense but also acknowledged the lack of intent to kill, emphasizing the tragic and spontaneous nature of the assault that led to Leiton Rowlands’ death.