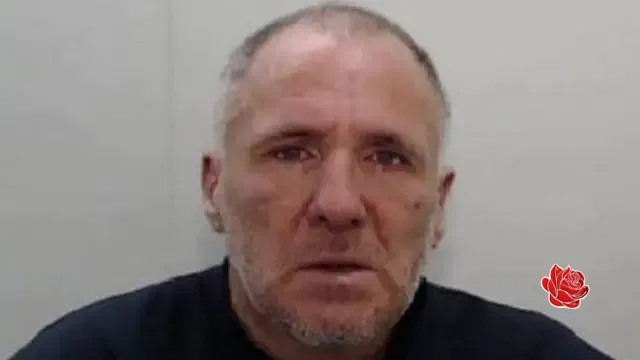

Ronald Castree's Social Media Accounts

Know a Social Media Account Linked to Ronald Castree?

Want to add information? Log in to your account to contribute accounts and phone numbers.

RONALD CASTREE CONVICTED OF LESLEY MOLSEED MURDER IN ROCHDALE AFTER 32 YEARS

In November 2007, Ronald Castree, age 54, was finally convicted and sentenced for the 1975 murder of 11-year-old Lesley Molseed from Rochdale, after evading justice for over three decades. Castree received a minimum sentence of 30 years for what the judge described as "a truly dreadful crime," stating he believed Castree would likely die in prison.Lesley Molseed’s body was discovered on Rishworth Moor in West Yorkshire. The case became one of Britain’s most infamous miscarriages of justice when Stefan Kiszko, a socially isolated man, confessed under pressure to the abduction and murder. Kiszko was imprisoned for 16 years before DNA evidence cleared him in 1991, revealing that semen samples from Lesley’s clothing did not match him, as he was infertile. Kiszko died in 1993, just a year after his exoneration.

New forensic technologies in 2000 generated a DNA profile linking Castree to the crime scene. The following year, investigators confirmed that a DNA sample collected from Castree during arrest in 2005 on unrelated charges matched the DNA profile from Lesley’s clothing with a one-in-a-billion probability.

Court documents also revealed that days before Kiszko’s trial, Castree had abducted and indecently assaulted a nine-year-old girl, leading to a separate conviction. During his murder trial, Castree attempted to hide this conviction from the jury and argued that the DNA on Lesley’s clothes might have become contaminated or that police had falsely implicated him.

However, the jury at Bradford Crown Court was not convinced. Mr. Justice Openshaw addressed Castree directly, stating, "You kept quiet whilst an entirely innocent man was arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced for this murder."

After the verdict, Lesley’s mother, April Garrett, who had reverted to her maiden name, expressed relief: "We are relieved that after so long our quest for justice for Lesley is now over."

Although Castree appeared outwardly as a caring father and a hard-working man, he concealed a dark secret. Behind his respectable facade, he was a paedophile and serial sex attacker, ultimately responsible for child murder.

In 1975, while his wife and her newborn were hospitalized, Castree abducted Lesley Molseed, who was known for her cheerful personality and gentle nature. He took her from a street in Rochdale as she was on her way to buy bread for her mother. He then drove her to a remote moorland, sexually assaulted her, and stabbed her multiple times in a frenzied attack before abandoning her body.

Castree then returned home and continued his life as if nothing had happened—a facade that lasted over 32 years until police arrested him in November 2007. On being detained, Castree reportedly said, "I’ve been expecting this for years."

Born in October 1953, Castree was the only child of Eric, an export clerk, and his wife Dora. Both parents passed away over ten years prior to his arrest. He married at a young age to Beverley, with whom he had a son, Jason, born in September 1975, despite knowing that Jason was not his biological child. Castree’s marriage was tumultuous, often marked by infidelity, and Beverley told Bradford Crown Court that there were always "three people in the marriage."

Castree, who admitted to being a serial adulterer, also took up taxi driving in the 1970s while still married. After the birth of Jason, Castree's wife was hospitalized with deep vein thrombosis, leaving Castree seemingly resentful of raising another man’s child.

The murder of Lesley occurred while Castree’s wife was at the hospital. Her abduction and killing of Lesley was described as a 'frenzied' assault, with Lesley, often called "Little Miss Chatterbox," being a small and vulnerable child with learning difficulties.

Lesley’s mother, April Garrett, recounted her last moments with her daughter and her fears when she realized Lesley was late returning from shopping.

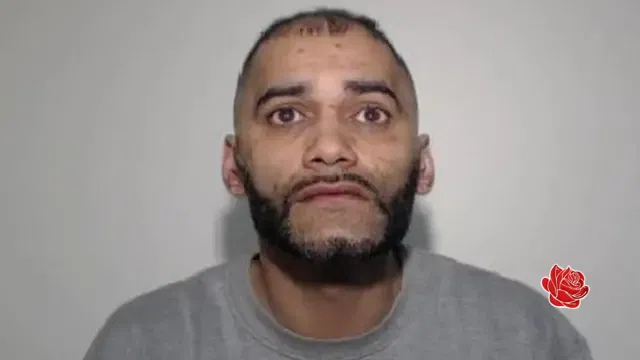

Initially, police suspected Stefan Kiszko due to his profile as a misfit and previous confessions, which he later recanted. The wrongful conviction deeply affected him; he was mentally underdeveloped, diagnosed with sexual underdevelopment, and was found with suspicious materials, leading to his conviction.

In the late 1980s, Kiszko’s case was revisited, and new evidence cleared him of guilt. He was released in 1992 but died from illness in 1993. Kiszko’s innocence was ultimately confirmed posthumously, and the case highlighted judicial errors.

It took another 15 years for Castree to be identified as Lesley’s real killer. His personal life fell apart, with his wife leaving him and their divorce proceeding in the mid-1990s. He later married Karen Curtin in 2004, with whom he had stepsons; one of the children was only eight years old at the time.

In 2005, a routine DNA test—done after Castree’s arrest for an unpublicized offence—led forensic scientists to match his DNA from samples taken with the biological evidence from Lesley’s case, despite her clothing having been destroyed after Kiszko’s wrongful conviction. Trace evidence stored on sticky tape used to lift semen from her underwear was crucial to establishing the match.

Castree attempted to explain away the DNA evidence with bizarre claims, including accusations that police had threatened to frame him for Lesley’s murder, despite police records indicating he was a suspect for a different incident in 1979. He also suggested that his DNA contamination could have resulted from interactions with Lesley’s mother and sister.

The jury rejected his explanations, leading to his conviction after 32 years. Castree showed no visible emotion as the verdict was read in the crowded courtroom.

His conviction marked the final chapter in the wrongful imprisonment of Stefan Kiszko, who had served 16 years for the crime before being exonerated. Kiszko’s case became a symbol of judicial failure and the importance of forensic evidence in ensuring justice.